St. Carlo Acutis

St. Carlo Acutis

Explore the Saints

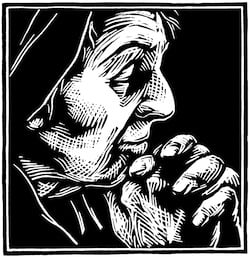

St. John Chrysostom

St. John Chrysostom is a doctor of the Church, a bishop from the fifth century whose fiery and powerful preaching earned him the name “Chrysostom,” meaning “golden mouth.”

He was born in 347 in Antioch, Syria, the only son of a commander of imperial troops. His father died when he was still a child, thus John was raised by his mother, who modeled for young John a truly Christian life, devoting herself to a life of piety while upholding her family obligations.

John’s mother provided the best education possible for her son, and John learned rhetoric from the master orator of Antioch, Libanius. Even as a young man, John outperformed the other students, and even surpassed his teacher in style and talent. In fact, as legend has it, Libanius was on his deathbed and asked who should follow him in leading the school. “John would have been my choice,” he said, “if the Christians had not stolen him from us.”

After completing his education, John poured his dynamic energy into pursuing a monastic life. He joined the community of hermits and monks living in the mountains near Antioch. John spent four years under close spiritual direction from a monk, and another two years living in solitude and prayer in a cave.

The harsh monastic diet of a hermit caused great harm to his stomach, forcing John to return to Antioch and plaguing him with ill health for the rest of his life. Upon his return to the city, he was ordained a deacon and assigned to assist the bishop with preaching at liturgy. For twelve years, he served the Christian community of Antioch through his preaching. Continually, he encouraged the Christians of Antioch to be a witness to their status-obsessed pagan neighbors and to provide radical love and hospitality to the poor. His homilies on Luke’s parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man are particularly poignant examples. John Chrysostom was never afraid to venture into political territory during his homilies, and more than once he called out the imperial family on their lavish lifestyle and decadence. To John, Christianity was not simply a private affair in the hubbub of public urban life. In John’s eyes, Christians were called to transform the metropolis.

In 398, John, against his wishes, was named bishop of Constantinople, the capital of the new Roman empire. As bishop, he scandalized the elite of the city through his Spartan lifestyle. Eschewing dinner parties and fine clothing, John provided for the poor and supported the relatively new invention of urban public hospitals. John particularly encouraged a Eucharistic devotion among his people, urging them to receive Communion as often as they could. John highlighted the Eucharist as the banquet of the heavenly city where rich and poor could meet as equals in Christ.

He was known for being able to speak to the hearts of people who felt stuck in sin—“If you have fallen a second time, or even a thousand times into sin,” he said, “come to me, and you shall be healed.” John converted many with his intuitive compassion for others, and his firm calls to repentance.

John spent his last years in exile for speaking out once too often against the sumptuous lifestyle of the Empress Eudoxia and the imperial capital. In revenge for his criticisms, the emperor and empress conspired with a faction of bishops who opposed John and had him removed from office and exiled deep into the region of Anatolia in present-day Turkey. Forced to march for three months to his exile, John suffered greatly on this journey, as the harsh elements and rough treatment taxed his already frail health. He kept up his correspondence until the end; his letters to his friend the deaconess Olympias are a precious record of his last days. He died on Sept. 14, 407.

John’s storied last words to his congregation were: “Violent storms encompass me on all sides. Though the sea roar and the waves rise high, they cannot overwhelm the ship of Jesus Christ. I fear not death, which is my gain; nor banishment, for the whole earth is the Lord’s; nor the loss of things, for I came naked into this world, and I can carry nothing out of it.”

In 1204, crusaders looted his relics from Constantinople and bore them to Rome. In 2004, Pope John Paul II returned some of these relics to the Eastern Church. Other relics of his rest in the reliquary chapel in the Basilica, where he is also depicted in two stained glass windows. One of these windows shows him contemplating a vision of St. Paul, whose writings were a favorite subject of his preaching. Additionally, John Chrysostom is portrayed in a stained glass window in the library of Moreau Seminary, below a symbol for the Eucharist, which he encouraged devotion to among his flock.

An overwhelming number of John Chysostom’s homilies have been preserved throughout the millennia since his death. He is considered the greatest preacher in the history of Christianity. The liturgy most often celebrated by Eastern Rite Catholics and Christians comes from St. John Chrysostom’s Eucharistic Prayer—his words have shaped liturgical worship for millions over many centuries. As a doctor of the Church, he joins the ranks of 37 other saints who are honored for how well they taught the faith in words and deed.

St. John Chrysostom, golden-mouthed doctor of the Church, who eloquently challenged your people to serve Christ in the outcast of society—pray for us!

Search Saints

St. Carlo Acutis

St. Carlo Acutis

St. Joseph of Cupertino

St. Joseph of Cupertino

Sts. Anne and Joachim

Sts. Anne and Joachim

St. Robert Bellarmine

St. Robert Bellarmine

Sts. Cornelius and Cyprian

Sts. Cornelius and Cyprian

Our Lady of Sorrows

Our Lady of Sorrows

The Exaltation of the Holy Cross

The Exaltation of the Holy Cross

Blessed Victoria Strata

Blessed Victoria Strata

St. John Gabriel Perboyre

St. John Gabriel Perboyre

St. Nicholas of Tolentino

St. Nicholas of Tolentino

St. Peter Claver

St. Peter Claver

Feast of the Birth of Mary

Feast of the Birth of Mary

St. Cloud

St. Cloud

St. Eleutherius

St. Eleutherius

St. Teresa of Calcutta

St. Teresa of Calcutta

St. Rose of Viterbo

St. Rose of Viterbo

Pope St. Gregory the Great

Pope St. Gregory the Great

Blessed Jean-Marie du Lau and the Martyrs of September

Blessed Jean-Marie du Lau and the Martyrs of September

St. Anna the Prophetess

St. Anna the Prophetess

St. Pammachius

St. Pammachius

Feast of the Beheading of John the Baptist

Feast of the Beheading of John the Baptist

St. Augustine

St. Augustine

St. Monica

St. Monica

Our Lady of Czestochowa

Our Lady of Czestochowa